As America entered the Great War in 1917, Uncle Sam encouraged all his hyphenated American nieces and nephews to join him in fighting this war to end all wars.

“You came here seeking Freedom,” he told the masses of immigrants living on our bountiful shores “and now you must help to preserve it!”

And on the home front nothing was more patriotic than the battle on food conservation.

“Food will win the war,” Uncle Sam proclaimed, exhorting all patriotic American women to help win the war in their kitchen by voluntarily restricting precious food commodities so that the dough boys and our allies would be well fed.

While we were fighting “over there” over here it was all out war on scarce wheat, meat, sugar and animal fats; it was, also all out war on anyone remotely appearing un patriotic, i.e. un American.

If conserving on wheat would help our fighting boys it was a small price to pay to show you were 100% American.

Enlisting the help of housewives by making them soldiers of the kitchen, women were on the front lines on the home front including my great-grandmother Rebekah and her daughter, my then 17-year-old grandmother Sadie

Pledge Drive

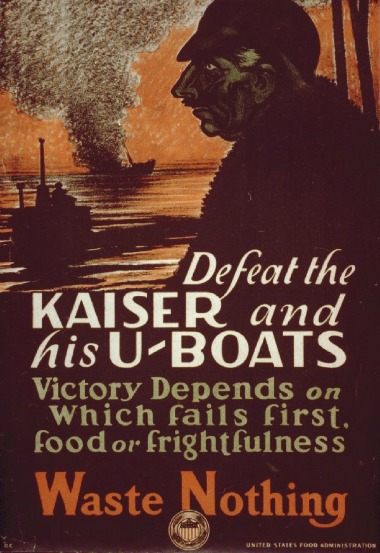

The newly formed the Food Administration relied on patriotic propaganda to reduce food consumption in the US. Uncle Sam persuaded, not forcing Americans to cut down on their consumption of white wheat flour and meat as well as butter and sugar.Besides pledging allegiance to the stars and stripes, American women were asked to sign a pledge card promising to restrict their food choices.

Young girls were eagerly sought after to be part of Wilson’s infamous Call to the Women of the Nation” and my then teenage grandmother Sadie eagerly stepped up.

Literally

One way that Uncle Sam was able to persuade people into volunteer food conservation efforts was to sign a pledge card.

When the first Pledge Drive began in late October 1917, my high school student grandmother answered Uncle Sam’s call to canvass her Brooklyn neighborhood collecting signatures. From October 29th to November 4th, Sadie and her classmates tramped up and down Bedford Avenue, brownstone to brownstone, house to house, encouraging housewives to sign the pledge cards during Food Pledge Week.

No one wanted to be accused of having questionable dietary choices which became synonymous with being unpatriotic. Just as the government had whipped a very reluctant country to go to war in order to “make the world safe for democracy,” so Uncle Sam became skilled at food shaming the American public.

Americans agreed: We shall cheerfully deny ourselves.

We Answer to a Higher Authority

Corn as well as other grains were encouraged as substitutes for scarce wheat. WWI Food Conservation poster

Returning home from school one late October afternoon in 1917, my then teenage grandmother Sadie found her mother standing at the coal cook stove in the spotless, onion scented kitchen, rendering chicken fat (schmaltz) in the “fleyshik” (meat) frying pan, and frying cheese blintzes in the milkhik (dairy) pan, never ever confusing one cast iron pan for the other.

The rambling house in Williamsburg Brooklyn was alive with the odors of burning carrots, frying onions, cooking cabbage and fermenting sauerkraut ( now patriotically called liberty cabbage.) Without even looking up from the stove, Rebekah handed Sadie a piece of challah, schmeered with schmaltz, – a nosh before dinner.

Sadie was bursting at the seams to tell her mother not only what she had learned in her Home Economics class and how it could help win the war effort, but the importance of the pledge drive.

Sitting at the oil-cloth covered kitchen table nibbling on the rich, greasy, bread, Sadie excitedly explained to her mother how scientists had devised new rules of nutrition classifying food into groups like proteins and carbohydrates and were now telling folks what was good for them to eat based on the foods recently discover chemical make up.

Relying on these principles of new scientific nutrition, Uncle Sam had established rules for how and what to eat for the war effort.

Happily cooking with Crisco was not only kosher, economical and digestible it was patriotic. Whether baking challah or pastries, Jewish housewives could avail themselves of Crisco. Vintage Crisco ads WWI 1917

Home economists from the newly formed U.S. Food Administration had prepared a hefty textbook for high school students explaining not only the theories of new nutrition, but devising war-time recipes and menus which would use substitutes for scarce precious wheat, beef, butter, and sugar.

We All Must Do Our Share

Holding up a pledge card, Sadie explained how Uncle Sam was now politely asked housewives to voluntarily sign pledge cards to obey the food conservation rules set out by the Food Administration, suggesting one wheatless day a week, one wheatless meal a day, one meatless day a week, and one meatless meal each day.

WWI Pledge card from the Food Administration signed by First lady Edith Wilson.The second pledge card campaign in late October 1917 managed to sign up nearly half a million out of 24 million families.

Proudly she told to her mother that Mrs Wilson was the first woman to sign this important food pledge card, setting the example for all American women to follow.

“There was no better way to support and show your Americanism than to sign a pledge card like our first lady,” Sadie urged her mother.

Besides which, nowadays dietary transgressions, Sadie implied were close to treasonable. “But all a patriotic housewife had to do was walk right up and ask Uncle Sam to show me how!”

Separate But Equal

But Rebecca had already signed a pledge card of sorts.

She had walked up to her own higher authority, the laws of Kashruth, the ancient Jewish Dietary laws and asked them to show her how.

In an Orthodox Jewish household like my Great Grandmothers, the only important rule- one that was non negotiable was the time-honored rule of Kashruth, keeping kosher an elaborate system of rules that dictated the kinds of foods that were permissible to eat and even the way the foods are prepared.

She needed a scientist or Uncle Sam to tell her about food, like she needed “a hole in the head.”

But no one wanted to be thought unpatriotic. In an age of heightened xenophobia this Russian immigrant dared not be thought un-American. Besides, if a mensch like Uncle Sam asked, who could refuse?

A proud citizen she embraced her Americanism. By signing the pledge card, she joined thousands of immigrant Jewish housewives all over Brooklyn who would hang the cards in their windows attesting to their oath (“the service tag of American women”)

Meaning of America

One couldn’t say that our land-of-the-free-government didn’t take the needs of the melting pot masses in to consideration.

Thoughtfully, Uncle Sam had printed out a whole batch of pledge cards especially for his “Hebrew Sisters” conveniently translated into Yiddish, so that they would understand what they were signing.

Along with the door to door canvasing the cards were distributed in the local synagogues, along with government posters in Yiddish proclaiming, “You came here seeking Freedom. You must now help Preserve it – Waste Nothing!”

This was all part of President Wilson’s Committee on Public Information in an effort to solicit support for the war.

As part of the program, an army of volunteers called the Four Minutemen gave brief speeches typically 4 minutes long to spread support for the war, speaking wherever they could find an audience such as at theaters, nickelodeons, lodges and churches.

A Four Minute Shtik

The local Four Minute Men organization tried to tailor speeches to immigrant communities.

In N.Y.C alone some 16 hundred speeches addressed half a million people each week in their native tongues. Italian was popular but it came in second to Yiddish.

Yiddish speaking Four Minute men spoke at Yiddish theaters, playhouses, and synagogues, including my great-grandparent’s temple.

The jingoistic talks were called “The Meaning of America” and the appeal to patriotism was essential. Utilizing themes of shared sacrifice and responsibility of citizenship encouraging every American, adult and child, to “do your bit.”

This was the Great Crusade, the most insistent call for citizenship and participation the nation had ever seen.

The Great Crusade.

We would sacrifice for our Dough Boys – the crusaders of democracy. Vintage photo Ladies Home Journal

A handsome rosy-cheeked shtarker strode deliberately into the synagogue meeting room filled to capacity with Sisterhood members, and without any kibitzing got down to business.

“I am glad to join you in the service of food conservation for our nation,” he read aloud from a pledge card to the group of mostly former Eastern European Jews like my great-grandmother who listened intently. “Who could refuse? See what it says? You do not need to promise wheatless day.”

“Remember too, this pledge card is sent direct to Washington. It helps our boys and is an honor for every patriotic American woman.”

Continuing in Yiddish, the young man explained that the American people should eat plenty, but wisely and without waste.

“It is our job, yours and ours to save food so that millions of starving people in Europe may have something to eat. (He got the Jewish guilt down right.) To buy or cook to eat more than you need to waste a single morsel of food that can be used –is a crime.”

“It was,” he said without a bit of irony, “the greatest crime in Christendom!”

It’s a Shame

It was only later when Sadie carefully read the card that she was asking her neighbors to sign, that she was shocked to see that in fact it wasn’t very kosher at all. Not only was it full of incorrect words in the translations, but her kosher mother had signed an oath promising to try to eat (in lieu of meat) shellfish, a violation of Kosher law.

The melting pot really started to simmer over that.

But if that wasn’t enough, an official circular from The Food Administration, signed by Mr. Hoover himself, was sent to the Sisterhood of the Synagogue-of which Rebeka was a member of good standing, urging them to convince the congregants to give up, just for the time being, mutton (forbidden ) and pork (really forbidden!) Rebeka also a member in good standing of the melting pot, really started to boil over on this one.

Thanks a lot Uncle Schmulie!

You Might Also Enjoy

Women and Food Will Win the War- WWI PT I

© Sally Edelstein and Envisioning The American Dream, 2016. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Sally Edelstein and Envisioning The American Dream with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Fascinating!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gee, if they had only taken the “duct tape” pledge we might have WW1 sooner. I mean, because we all made this pledge, George W Bush could tell us all in May 2003 that the world was again safe for democracy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Women and Food Will Win the War – WWI | Envisioning The American Dream

Pingback: Food during Wartime, Part 1: Messaging – LAURA's Data BLOG